We spent the first half of our Color 101 series covering the basics of human vision, cameras, and displays, which together form the key factors in any motion-imaging workflow. Having done this, we’re now ready to build on this foundation and begin exploring the core philosophies, tools, and techniques of color grading. We’re going to begin this exploration by discussing one of the most critical (and most overlooked) choices in any grade: working with our images in a scene-referred versus display-referred context. If you’re unclear about what this means, or its implications for your images, read on!

The Basics

To understand what we mean when we refer to scene-referred or display-referred workflows, let’s recap a few basics.

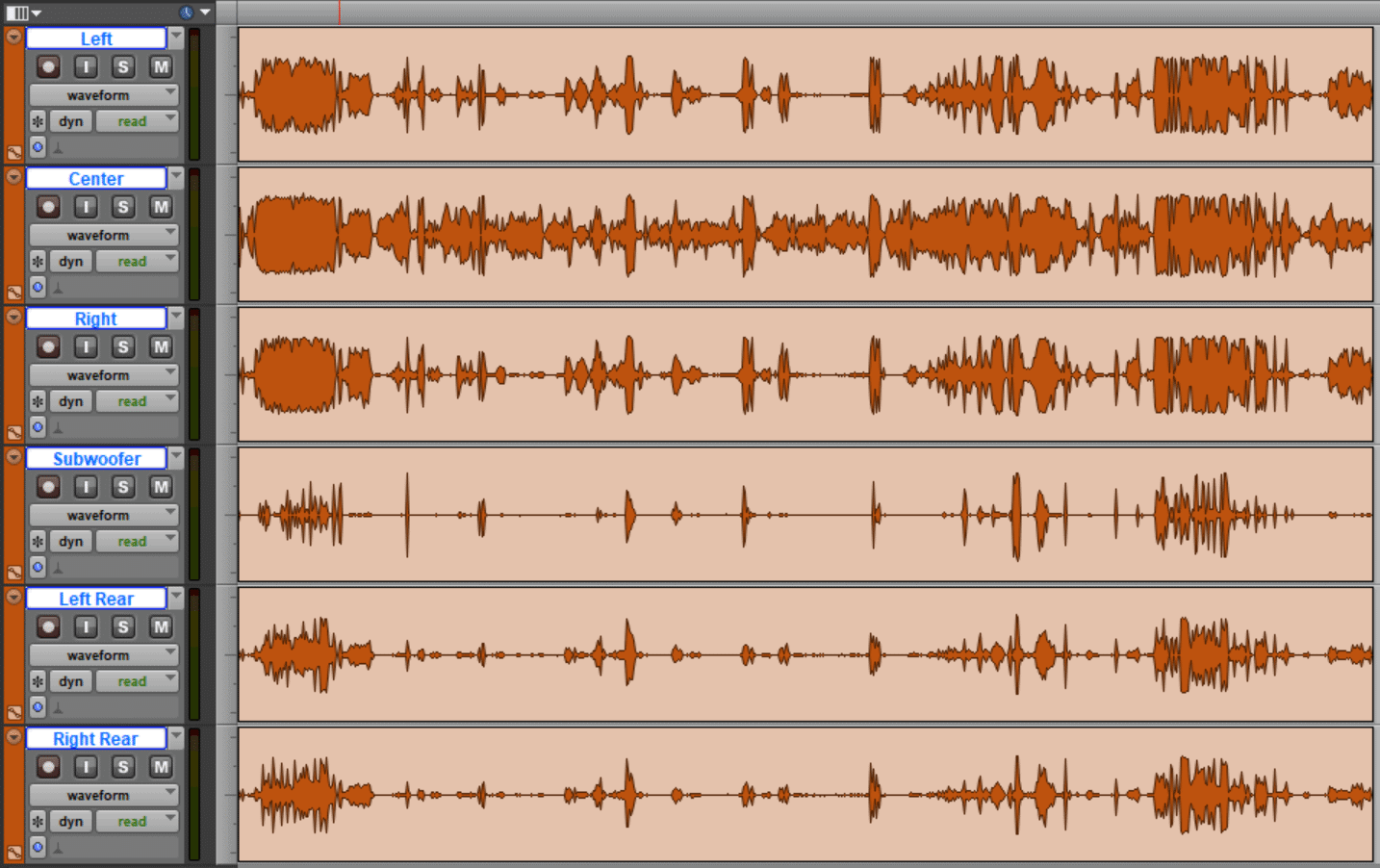

We learned earlier in this series that any imaging system — whether a camera, a display, or our own eyes — interprets light and color in its own way, and that we can measure and express these unique characteristics in terms of their gamma (or tone curve) and gamut. Collectively, this gamma/gamut pair defines a device’s color space. Once we know the color space of our source(s) as well as that of our display, we can make an accurate mathematical translation from one to the other.

So, in simplest terms:

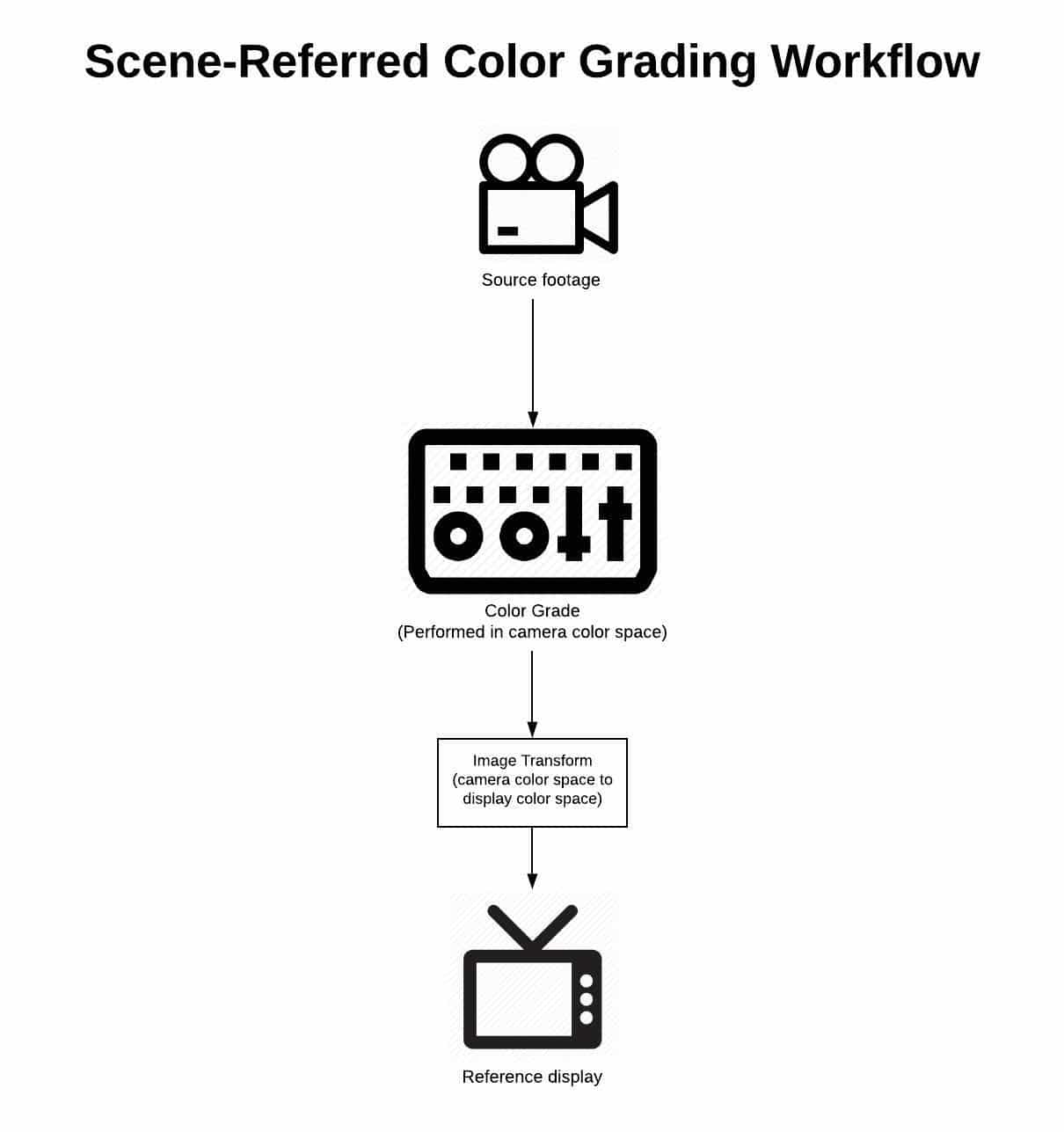

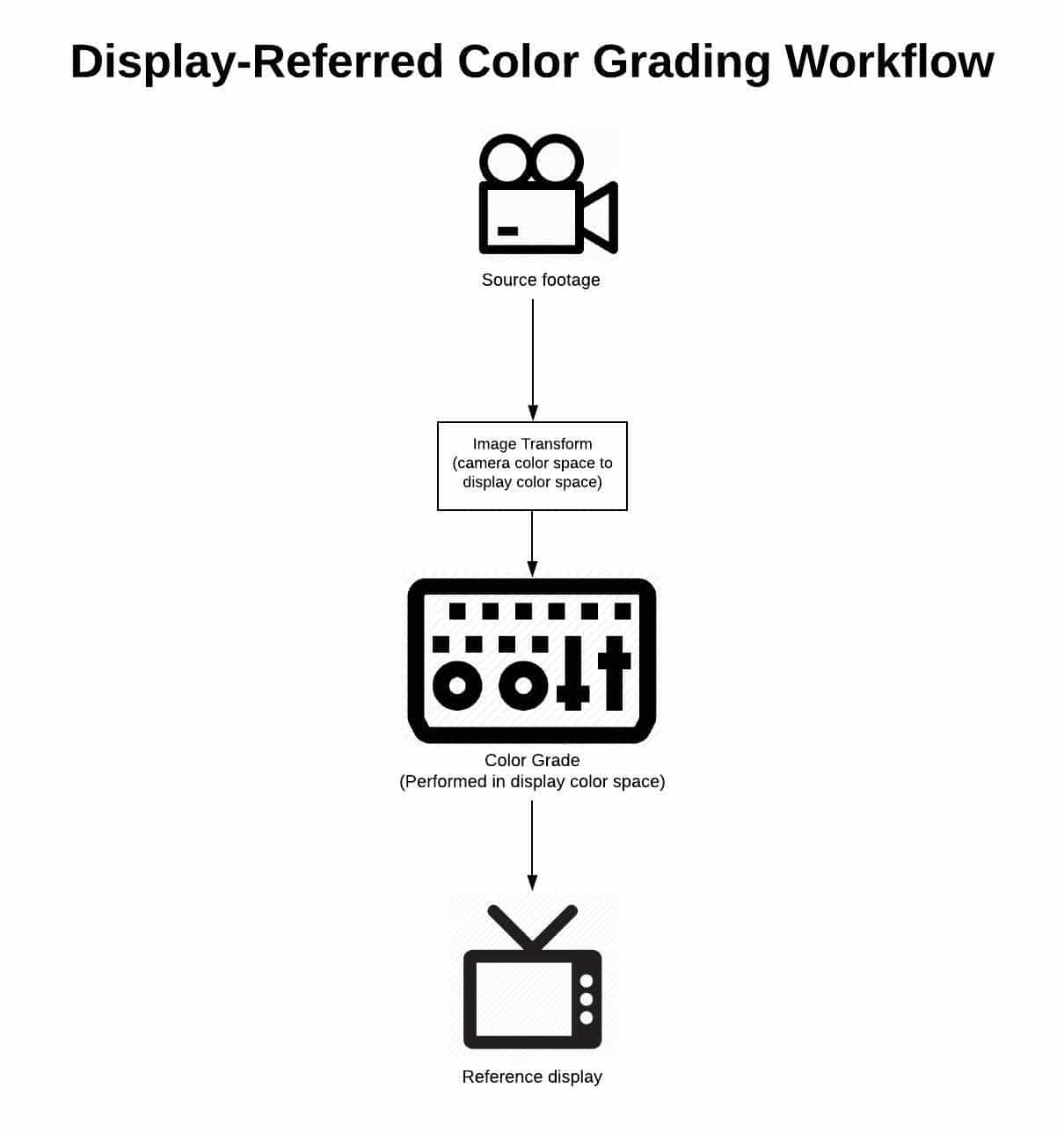

A scene-referred workflow is one in which we manipulate our images prior to their transformation from camera color space to display color space. A display-referred workflow is one in which we manipulate our images after they’ve been transformed from camera color space to display color space.

Easy enough, right? But what impact do these different approaches have on our images? How can we know which is right for us? And how can we practically implement this knowledge in our workflows?

To answer these questions, we need some historical context.

A Bit of History

Modern color grading tools and techniques represent the union of two distinct forms of image mastering: color timing and color correction.

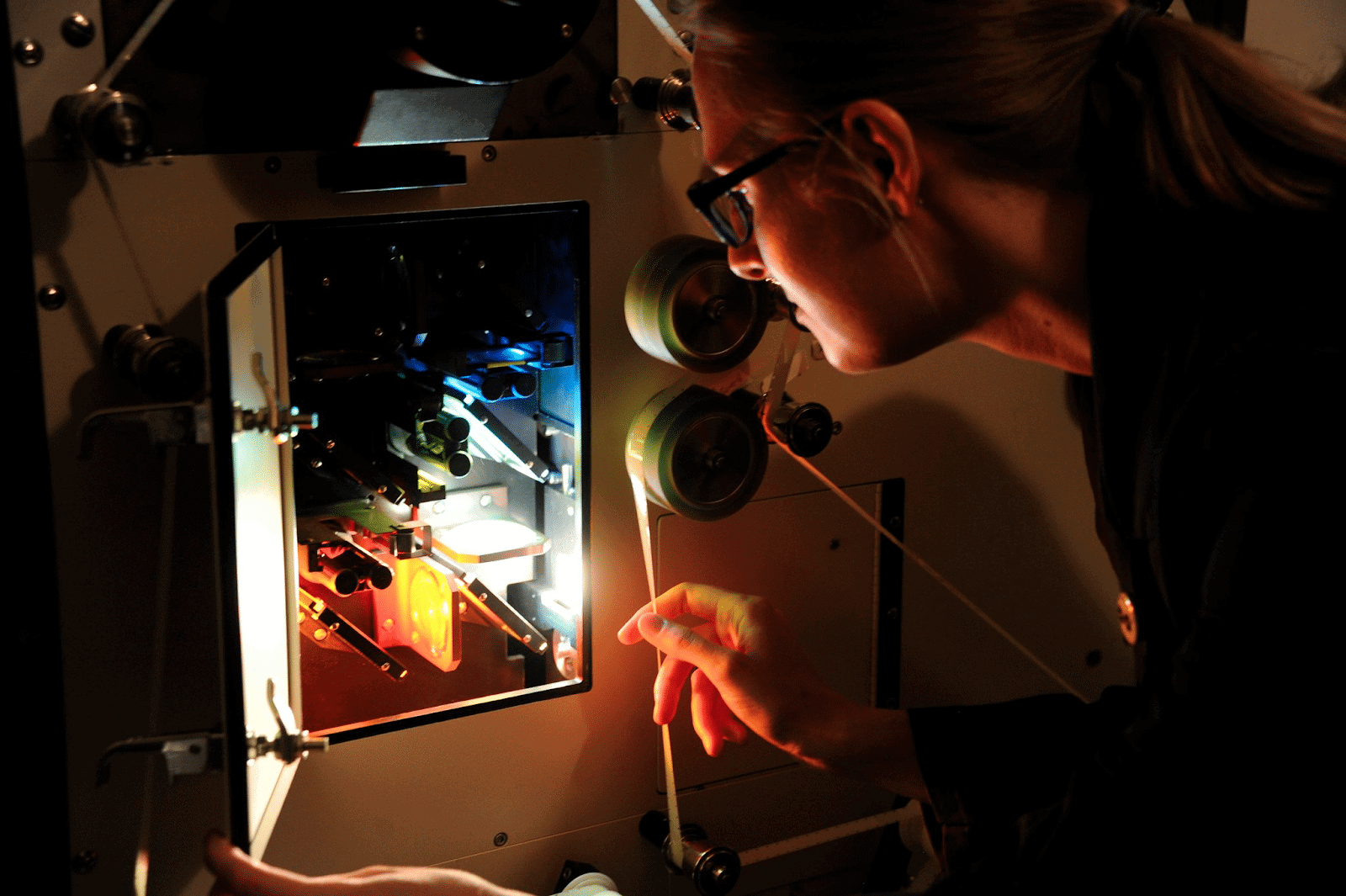

Color timing is a craft nearly as old as filmmaking itself — until the last few decades, it was the sole method by which film images bound for theatrical release were mastered. It is a photochemical laboratory process which manipulates film images through the use of physical light, and it is inherently scene-referred in nature.

Color correction is a younger discipline, made possible with the advent of video imaging. It is an electronic process which manipulates images by altering their encoded signal. Color correction was designed to tweak broadcast images which were already in display color space, and as a result it is an inherently display-referred process.

The history of modern color grading can be understood as a slow merging of these two methodologies, with milestones including telecine (video capture and electronic manipulation of film negative), digital intermediate (digital manipulation of film negative before being printed back to film positive), and the rise of digital cinema cameras. Today, the fusion between color correction and color timing seems complete. Practitioners of both are given the same title (colorist), use the same software, and are expected to be capable of working with film as well as broadcast images. Even the terms themselves have been largely discarded in favor of the more-inclusive heading of color grading.

But the discrepancies between the techniques and philosophy of each discipline are still with us, and can have a huge impact on our work. The choice between working display-referred and scene-referred is a perfect example. In order to successfully navigate this choice, we need to understand the ramifications of each approach, and make a conscious decision in support of our creative vision. So let’s take a look at the pros and cons of each.

Pros and Cons

Display-referred workflows

As we’ve learned in this series, all images undergo a multi-part journey from sensor (or film negative) to screen. A display-referred workflow operates on its images at the very end of that journey — following the transform from camera color space to display color space.

There are several benefits to working in this way. First, it requires virtually no knowledge or implementation of color management — meaning accurate technical transformation between color spaces. It also allows for grading to begin as soon as shots are loaded into the colorist’s software, with virtually no prep or setup required. Finally, with everything being done by hand, it generally feels highly tactile and creative.

These benefits are alluring enough that many colorists and filmmakers never look past them, but they come at high cost, both to the process and the end result. For starters, once transformed into its display state, an image loses much of its dynamic range and color information, affording the artist less flexibility to make clean manipulations. Equally problematic, displays interpret light and color differently than our eyes do, so an image transformed into display color space responds to adjustments in a very non-intuitive way. For example, in display space, operations as simple as an exposure adjustment require the careful manipulation of several different controls in order to get a perceptually linear response. Finally, because they’re not supported by good color management, display-referred workflows place too much burden on our eyes and display — both of which can lie to us in a variety of ways.

Scene-referred workflows

In contrast to display-referred workflows, scene-referred workflows operate on their images in the state they were captured in, i.e. prior to their transformation from camera color space to display color space.

One of the key benefits of scene-referred workflows is the consistency they afford. Because we’re operating upstream of a global transform, images tend to flow from one to another more easily. Working scene-referred also allows for more intuitive adjustments, because we’re operating on the image in a color space similar to that of our vision system. Unlike in a display-referred environment, operations such as exposure and color temperature shifts can be made cleanly and simply with a single knob. Finally, scene-referred workflows give us full access to the dynamic range and color information captured in-camera — much of which is truncated by the time the image is transformed into its display state.

Sounds like the superior choice, right? But what about the cons of this workflow?

There are two key cons to this workflow, which are enough to deter far too many filmmakers from using it. The first is that it requires us to learn the basics of our image’s journey from sensor to screen. The second is that it requires us to lay a proper foundation in our grade before we begin turning knobs. Both of these take time, and neither are very sexy. But the truth is that we owe this diligence to ourselves, our collaborators, and our images. The good news is, you’re more than halfway there by taking the time to read through this series!

Let’s wrap up by looking at the fundamentals of building a scene-referred workflow for your next grade.

Building a Scene-referred Workflow

Building a scene-referred workflow is simpler than it seems: all you’ll need is an edit consisting of footage from a professional or prosumer camera captured in a log format, and a good color grading application such as Blackmagic Design’s Davinci Resolve.

Step 1: Ensure you’re working with footage straight from the camera

When we’re grading, we want access to any and all color information captured on set, so the first step in setting up your grading workflow should be to ensure your timeline contains camera-original media, rather than proxies, transcodes, or exports. These will generally contain less information than the original footage, and often will have LUTs or temp color “baked” in, all of which compromise your ability to master the strongest possible image.

While a discussion of your overall post-production workflow is beyond the scope of this article, I encourage you to test and work this out well in advance, including a plan for relinking to camera-original material if you decide to use a proxy or “offline” workflow.

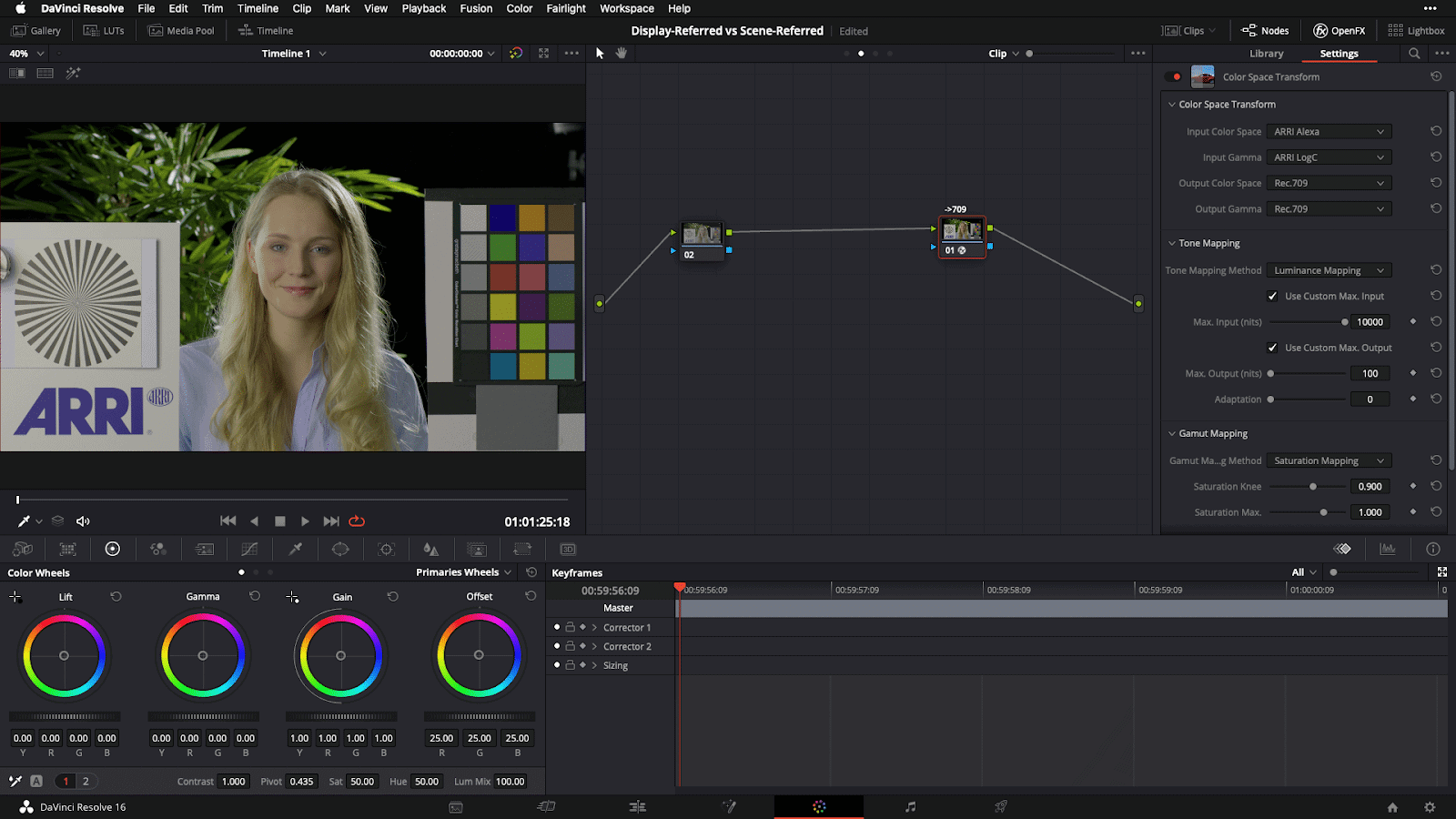

Step 2: Decide on how you’ll map from camera color space to display color space

There are many ways to transform your images from their camera color space to display color space, including LUTs, and Resolve’s Color Space Transform tool, and manual adjustment. In the case of raw formats such as R3D and ARRIRAW, you can even choose to unpack (or debayer) your raw images directly into display space. Each of these carries its own benefits and caveats, but here are the key criteria for choosing and deploying a transform that will properly serve your scene-referred workflow:

- We need to be able to control where in our image pipeline it’s deployed. This disqualifies doing our transform at the initial debayer stage, because once we’ve done so, we have no access to the camera-original scene data while grading.

- The transform should be technically sound, meaning it’s set up to receive an image in a color space matching that of our camera (e.g. Arri LogC), and to accurately transform that image into the color space of our display (e.g. Rec 709).

- The transform should be consistently applied at the same point in the imaging pipeline for all shots in your timeline.

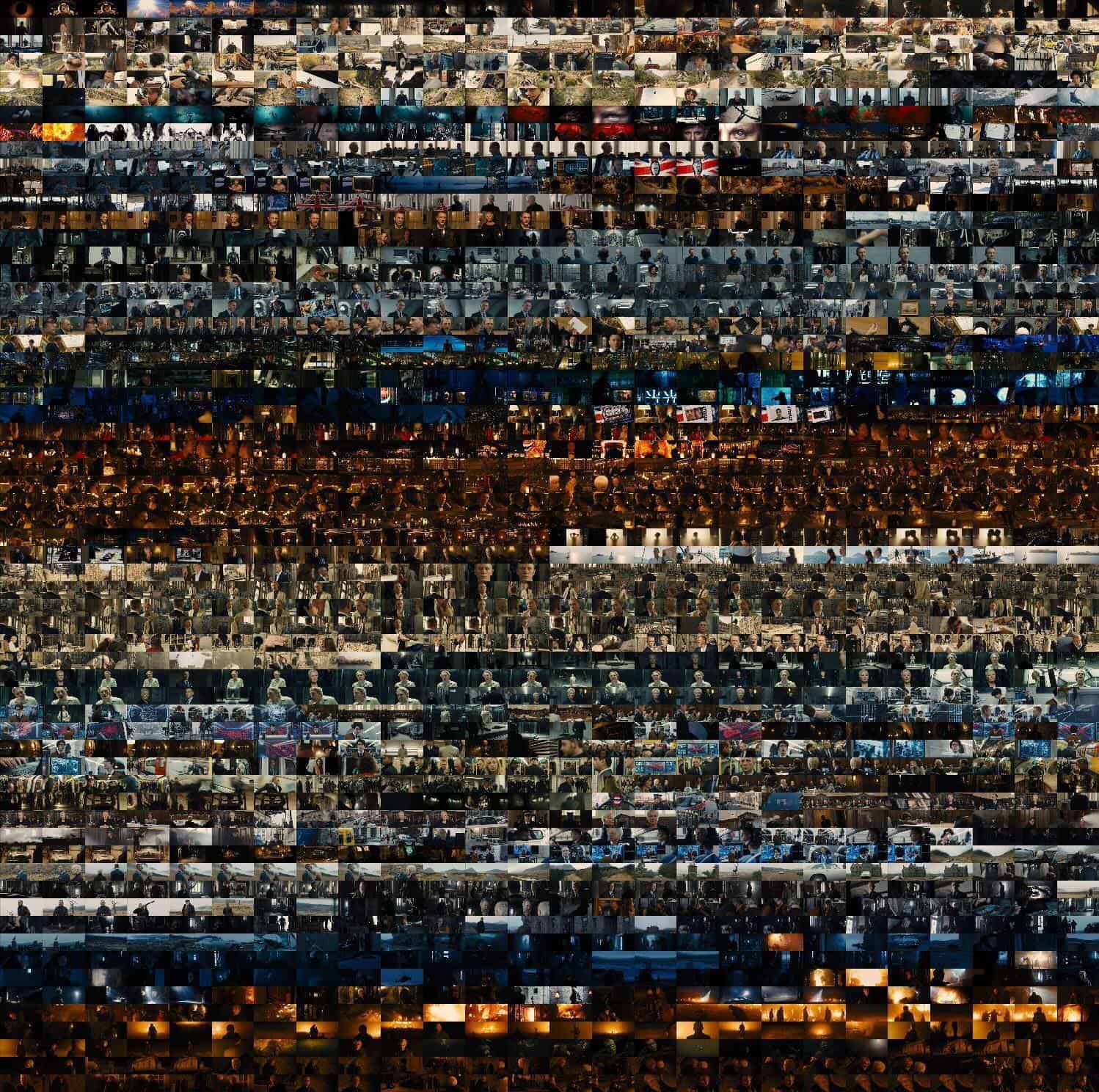

Step 3: Do your grading prior to your transform from camera color space to display color space

Once you’ve set up your transform in step 2, all you have to do is ensure you do your grading prior to this point in the image pipeline, such that the transform is always the last operation to take place on your image. In Resolve, this simply means creating nodes to the left of this final output transform.

It’s worth noting that if you’re used to working in a display-referred context, your controls will react differently than what you’re used to. But with a bit of practice, you’ll soon find doing your grade in-camera color space to be simpler, more intuitive, and to produce better-looking images.

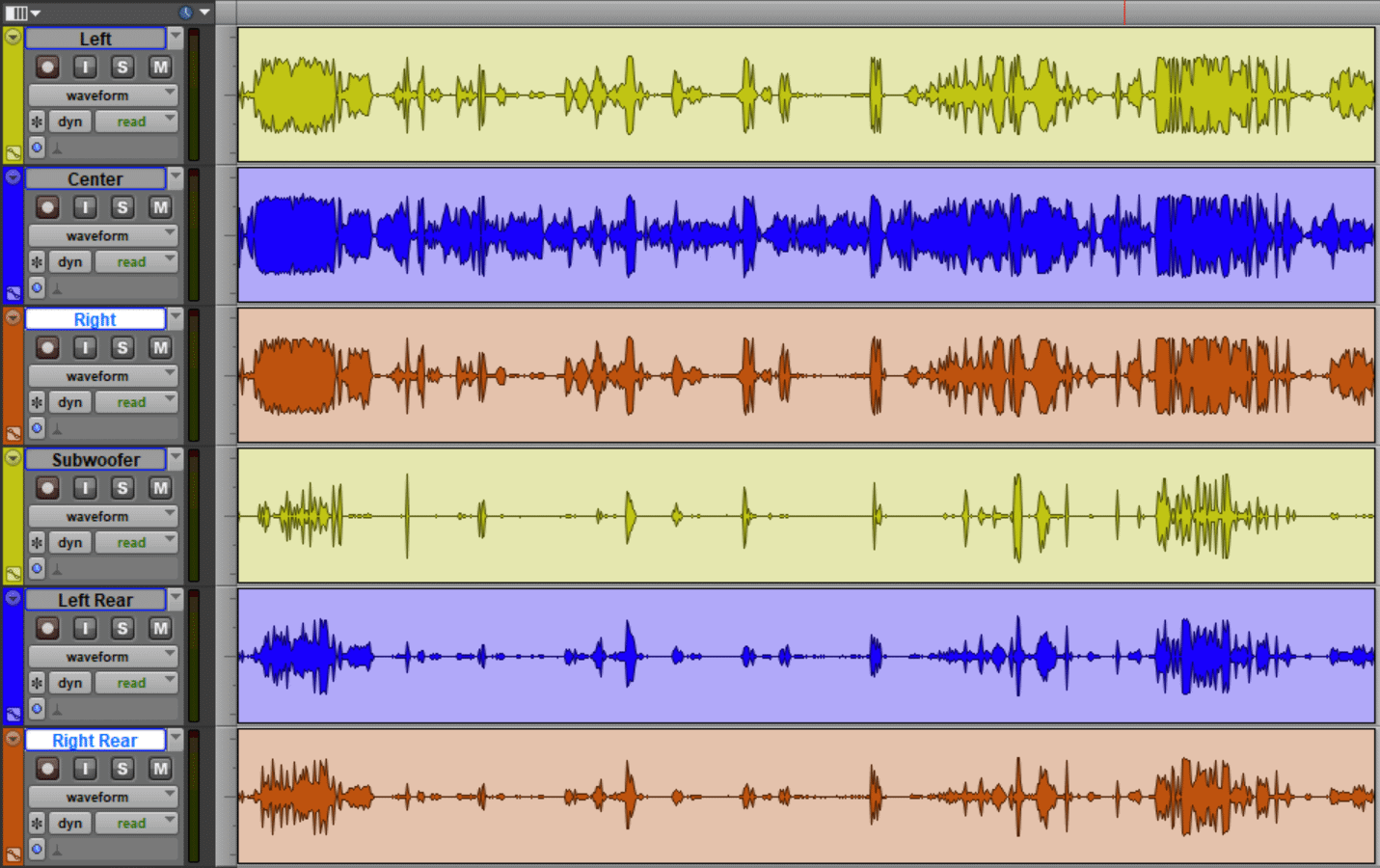

[Caption: Example scene-referred grading setup in Davinci Resolve, demonstrating a Color Space Transform from Arri LogC camera color space to Rec709 display space]

Closing

I hope it’s clear by now that the advantages of scene-referred workflows far outweigh the convenience of working display-referred. This advantage gets even larger when we consider the increasingly common need to strike deliverables for multiple displays. With a robust scene-referred workflow, we can simply target a different output for our grade, whereas in a display-referred workflow, we essentially have to start over, making subjective adjustments by hand to try and match our look between two or more displays. Educating ourselves on scene-referred workflows and taking the time to set them up is a small investment that pays dividends every time.

Now that we understand the implications of working scene-referred versus display-referred, as well as how to set up a proper workflow for the former, we’re ready to get hands-on with what I call the “Desert Island” tools of color grading — the five basic tools you can accomplish nearly anything with once you understand them. We’ll be covering this in our next installment of this series — see you then!