For over a decade, Film Riot has been dedicated to helping aspiring filmmakers learn about all the tips and tricks that make Hollywood movies “tick.” But as every good filmmaker knows, understanding the foundational basics is paramount if you want to be successful at telling stories with the moving image. That includes understanding shot types in filmmaking.

The next few episodes of Film Riot will cover some of those basics. First up is: Shot Types.

The 5 Shot Types in Filmmaking

In this series, Ryan uses the metaphor of writing a sentence to describe filmmaking. Shots are the words, coverage would be the collection of words to form that sentence, and editing is the arrangement of those words to form your sentence. In this episode, Ryan covers five shot types:

- Shot Size

- Angle

- Framing

- Movement

- Focal Length

Shot Size

The shot types Ryan covers are not entirely exhaustive, but they cover the basics.

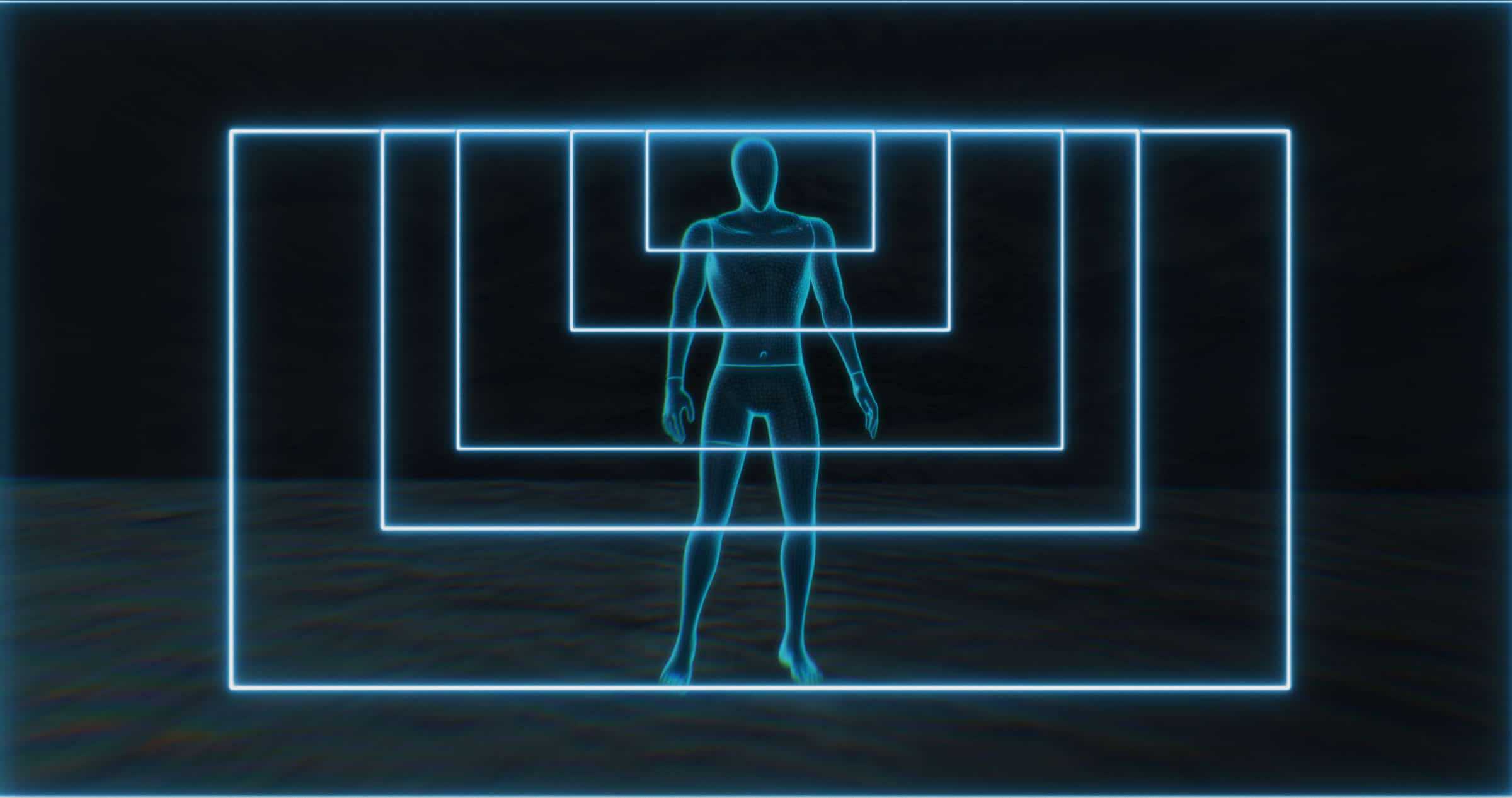

Extreme Wide Shot (EWS): a shot far from the subject that takes in the entirety of the area. Think of shots like a spaceship arriving to a planet; or the entirety of a castle and the large army arriving to sack it.

Wide Shot (WS): the subject is now in focus but they’re not filling the frame..

Full Shot (FS): a wide shot where your subject fills the frame, head to toe.

Medium Wide Shot (MWS): a “full shot” that is a bit closer such that the subject’s head and/or feet are cut off.

The “Cowboy Shot”: this is a version of the MWS that is called “the Cowboy” because the shot is cut off right where the person’s gun and holster would be.

Medium Shot (MS): the subject is framed from the hips up.

Medium Close-up (MCU): the framing is chest up. At this distance we can see the eyes more clearly, making the shot a lot more intimate. Many dialog scenes are shot with MCUs.

Close-up (CU): the subject fills the frame top to bottom. It is used sparingly and is often on people’s faces, but it doesn’t have to be. It can be that of a hand or prop.

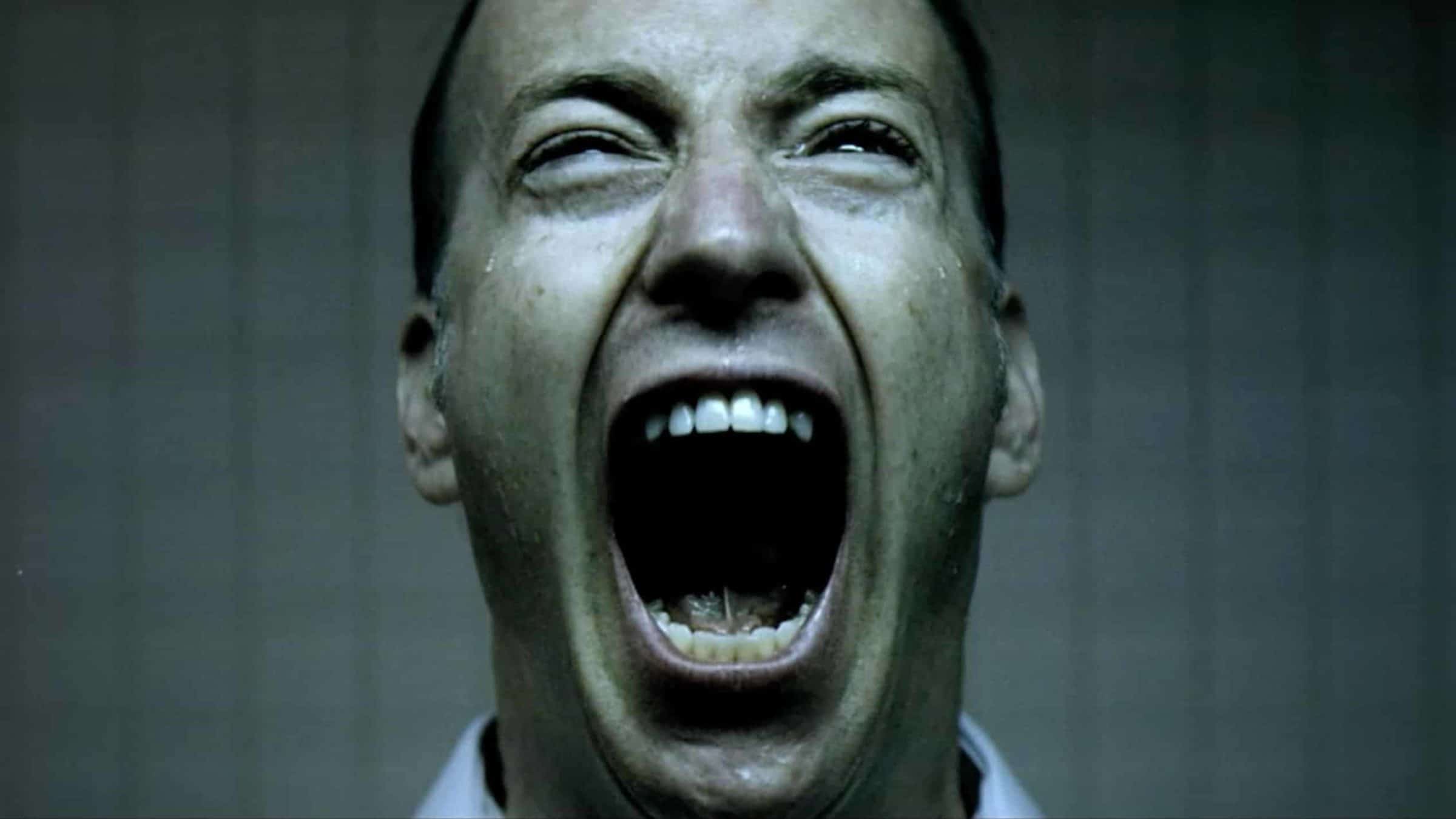

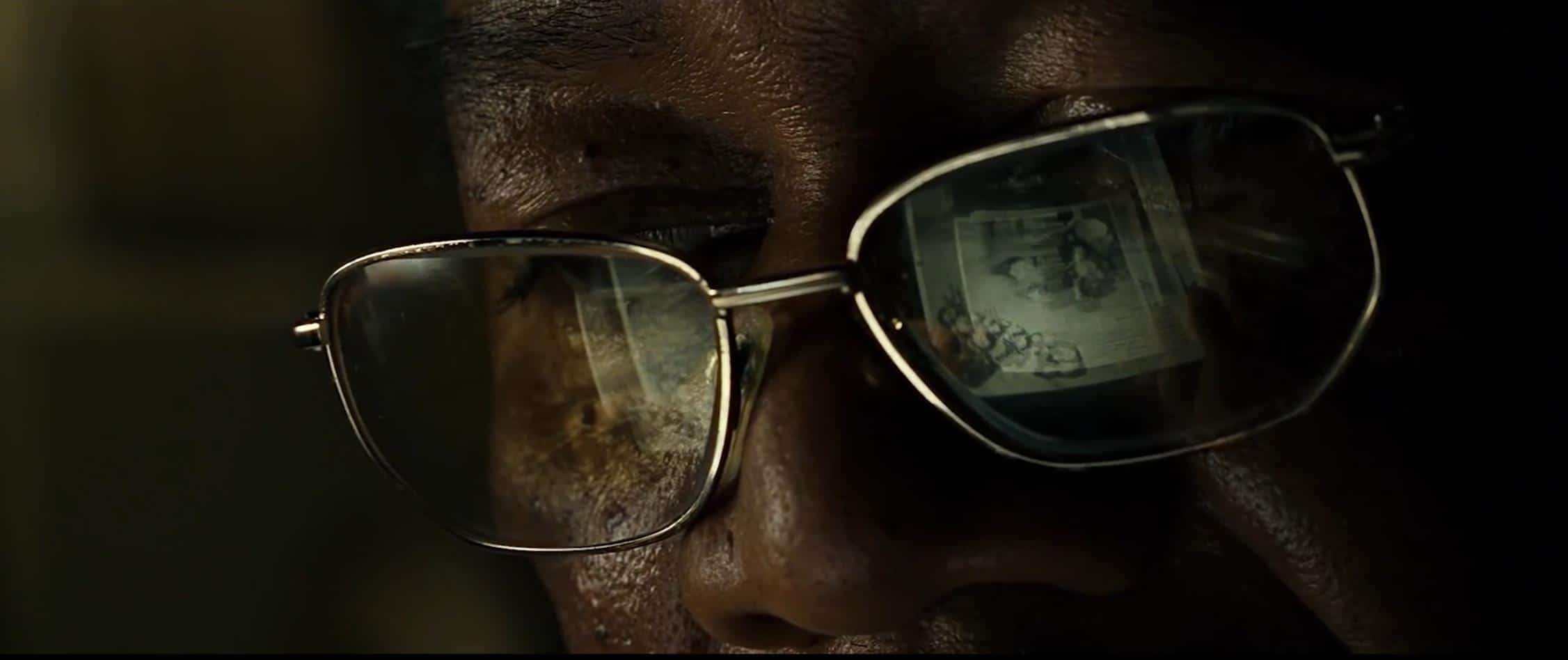

Extreme Close-up (ECU): an even closer (tighter) shot, often of a subject’s eyes or mouth. One of Ryan’s faves is this shot from “Se7en” where you can see Morgan Freeman’s eyes, as well as the reflection of the paper in his glasses.

Angle

This is the position of your camera relative to the subject in question.

Bird’s Eye View. Usually done as some form of wide shot, this is where the camera is directly over the subject. The shot below from David Fincher’s “Zodiac” is one of Ryan’s favorites.

Overhead. The camera is directly above the subject (essentially a tighter version of the Bird’s Eye View).

High angle. Just above eye level, but not directly above the subject. Usually used thematically to make the subject seem lesser or weaker.

Low angle. Often used to make the subject seem dominant and powerful.

Dutch angle. Shots where the camera is off-center and titled. Ryan loves how the director Brian De Palma.

Point of View (POV). There are two versions of this angle: the implied and the literal. The implied POV is when a character looks in a direction, then you show what they’re looking at.

The literal POV is when the camera is in place of the subject and you are literally seeing what they’re seeing. It’s often used in horror films. Another good example is ET peering through his costume as he walks down the street with the kids.

Framing

Everything that goes into how you compose a shot.

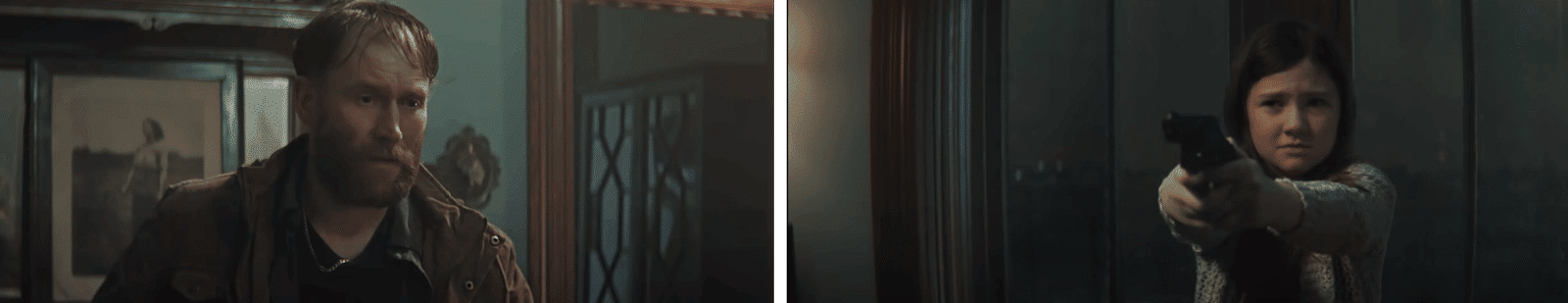

Clean or Dirty. Clean framing is when there’s nothing between the camera and the subject. Dirty is when there are people and/or objects between you and some key subject in the frame.

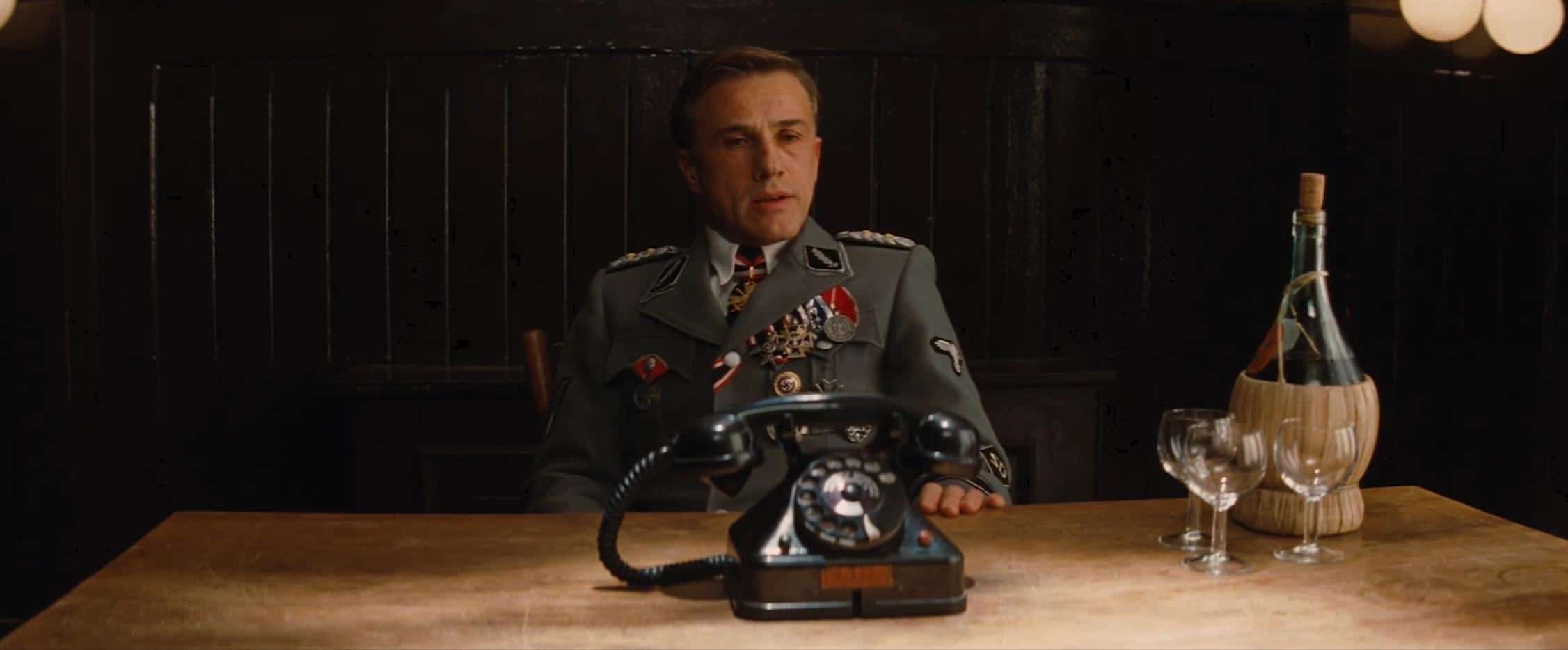

Over the Shoulder (OTS). Framing the camera so that you’re looking over the shoulder of one character to another.

Single and Two-shots. A “single” is when you just have one character in frame, and a two-shot is when you have (you guessed it) two characters in frame.

Movement

These are just the basic movement shots. Be sure to check out this episode if you want a full run-down.

- The Pan. The camera angle is changing, but the camera itself is not moving laterally.

- The Tilt. Moving the camera on a vertical access from up to down or vice versa.

- The Dolly. When the camera is placed on a dolly and moves towards or away from the subject, or laterally.

- Zoom. The subject becomes closer or farther away by changing the focal length. The background stays static.

- Tracking. This is where the camera tracks along with the subject, used during “walk and talk” scenes. The movie “1917” is essentially one long “tracking” shot.

- Crane or Boom shot. Movement of the camera when placed on a crane or boom arm.

Focal Length

Focal length refers to the lens. Lenses can have wide, medium, or long focal lengths. You can mix and match focal lengths with shot sizes to create different feels. This is more subjective and will change, depending on what you want your audience to feel.

For instance, a close-up of a subject’s face on a long focal length (i.e. you’re zoomed in) will feel very different than a close-up using a wide-angle lens.

The background is also greatly affected when you have a close-up on a wide vs long. Like this shot of Josh below. The close-up on the long throws everything completely out of focus. Whereas the CU with the wide-angle lens keeps more of the background more from completely blurring out.

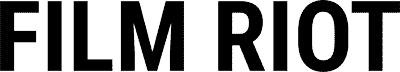

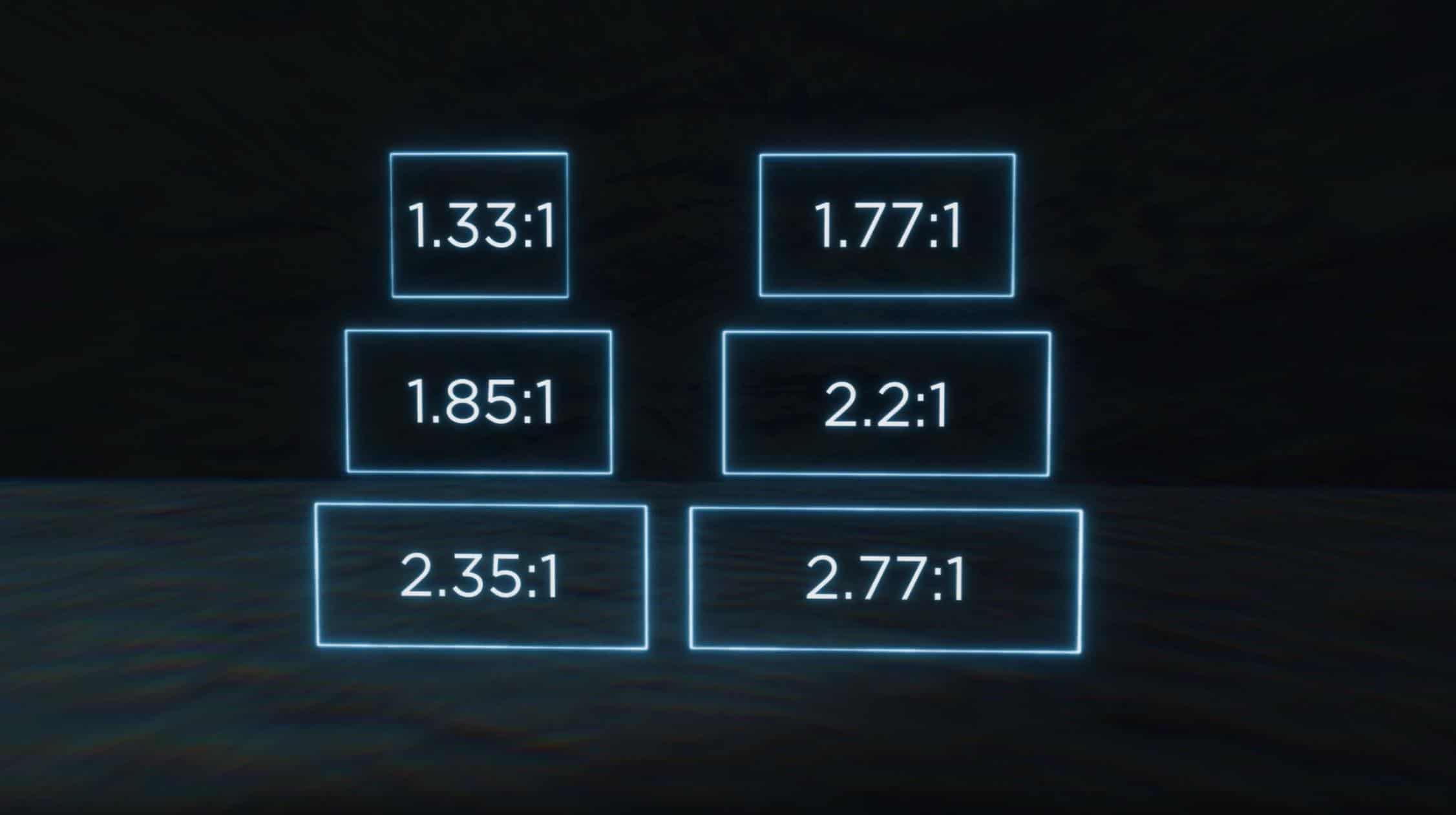

Aspect Ratio

It’s worth pointing out that the aspect ratio you choose for your film will affect which types of shots you use and how they are rendered on screen.

So there you have it. The basic “words” you need to construct your “sentence.” In case you missed it, here’s the episode that breaks down all of these shots.