In the world of filmmaking there are two “rules” which each share the same name—the 180 degree rule. One has to do with the position of your camera with respect to your actors/subjects. The other has to do with the relation of shutter speed and frame rate. Both “rules” are established to improve the viewing experience of your audience.

I put the word “rules” in quotes because like every other rule, they can be broken—if you know why you’re breaking them and it serves the story. However, IMHO, I see a lot of newbie filmmakers breaking these rules because they seemingly don’t know. So, I wanted to give some insight on these rules and why you should keep them—and why (and when) you’d want to break them.

Don’t cross the line

The first 180 degree rule I want to discuss is the 180 degree line. It states that if you have two subjects speaking to one another in a scene, draw an imaginary line through the middle of them. At all times, you need to keep the camera(s) on the same side of the line. If you cross that line, you’ve “crossed the 180.”

The purpose of the rule is to keep the audience properly oriented. If actor A on the screen is looking from left to right, and actor B is looking from right to left, they will be properly oriented as long as you stay on the same side of the 180 degree line.

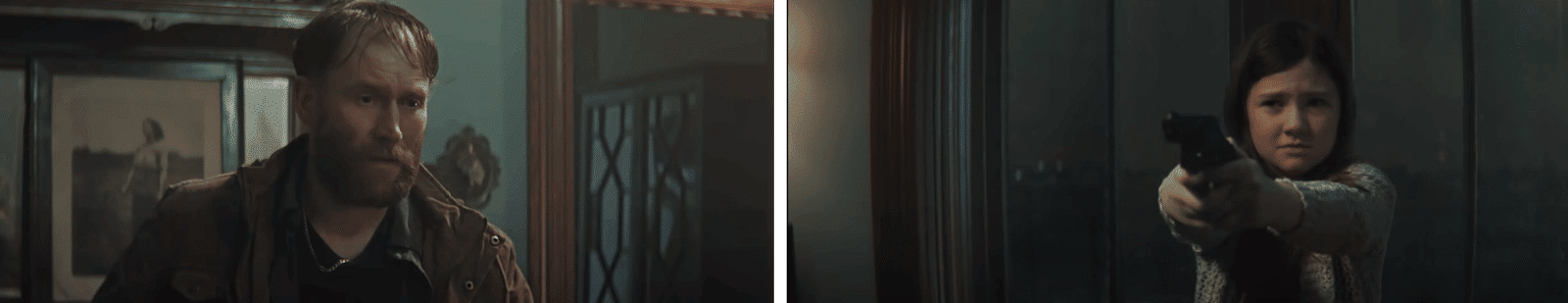

Here’s a clip from Ryan’s short “BALLiSTIC.” As you can see, both characters are oriented in a way that is natural and appears as if they are looking at one another.

But, if for whatever reason, you move the camera around for another part of the dialog, and you cross that 180, then both actors will be looking from either right to left, or vice versa, as you cut back and forth. That will be off-putting to the viewer, making it appear as if they are looking in the same direction instead of at each other. Using the scene from above, if you crossed the 180, the shot could look like this:

But it’s not just narrative films where this rule applies. You can apply it to event video or documentaries. If you’re shooting a wedding, ideally you would keep the camera on the same side of the 180, using the bride and groom as the two subjects. If in a documentary where you have two people talking on a 2-camera shoot, keep both cameras on the same side of the 180 for the same reason.

Here’s a great Film Riot episode that effectively and quickly illustrates it:

Breaking the Rule

Many newbies break this rule because they simply don’t know or aren’t aware. Many experienced people even break this rule from time to time because they may have had so many camera changes or are trying to get interesting angles, they forget where the 180 degree line started. Having a dedicated script supervisor (the person in charge of keeping track of how actors deliver lines, where props were for each shot, etc.) can help.

It usually makes sense to break this rule if you’re in a situation (usually an event video like a wedding) where you are forced to stand or set up your camera in such a way that it breaks the rule. Other than that, I can’t think of any other times I’d want to break this rule on purpose, unless for some reason I’m purposefully trying to disorient the audience. If you have ideas of when it would make sense to break this rule on purpose, hit us up on Twitter.

“Blurring” in the Line

The next 180 rule is the 180 degree shutter angle. I think most people break this rule because frankly, they just don’t know about it. I have to admit, until I started shooting with DSLRs way back when, and educating myself on how to properly shoot with then, I didn’t know it either. I knew what was considered the “normal” shutter speed setting for my camera (1/60 sec when I was shooting NTSC 29.97), but I didn’t know why. Hopefully this will give you some insight into this rule, as well as a better idea of when it’s a good time to break it, and when it’s not.

The Why—Proper Motion Blur

Plain and simple, the reason for the 180 degree shutter angle rule is to have proper motion blur. The rule states what your shutter speed should be set to relative to the frame rate of your camera. It’s very simple to figure out. Just double your frame rate. If you’re shooting at 30 fps, your shutter speed should be set to 60. [Note: this really represents the fraction 1/60th of second, NOT 60. But camera settings normally just use the denominator.

Also, as a side note, this 60 should NOT be confused with the 60i reference to a media format. When someone says they’re shooting in 60i, the “60” here actually refers to the number of interlaced fields. For every frame in a 30 fps shot, there are two interlaced fields, one odd and one even. So, for 30 frames, there are 60 interlaced frames, thus 60i. But that’s a blog post for another time.]

If you’re shooting at 24 fps, your shutter speed should be set to 48. However, many DSLRs don’t have an actual 48 shutter speed setting for video. So, use the closest one: 50. If you’re shooting at 60 fps, your shutter speed should be 120. And so on.

If your shutter speed is too fast or too slow, you won’t have proper motion blur. If it’s too fast, you get that staccato look popular in Ridley Scott battle scenes in “Gladiator.” If it’s too slow, the footage will look very soft and dreamy.

Rules are meant to be broken…sometimes

Okay, here’s where I may ruffle some feathers. I cannot believe how many DSLR videos I’ve seen that totally throw the 180 shutter degree angle out the window. Where it seems like every single shot is at a super high shutter speed. I see it a lot in the wedding cinematography industry, and I’m not sure why it’s so popular.

Having shot weddings for a number of years in my early days as a professional videographer, there were times when artistically a high shutter speed worked great. It’s popular to use on fountains to make the droplets of water look like diamonds falling. Or if the guests are throwing rose petals in the air, that high shutter speed staccato look can be cool. But I see it used for people just walking across the street, or hanging out in a bridal suite. For my taste anyway, it seems a bit overdone.

I know that in many circumstances, a high shutter speed is used when it’s particularly bright outside and the filmmaker is using a high shutter speed to compensate. A high shutter speed means less light is coming into the camera, and thus it’s a “trick” you can use if it’s too bright outside and you don’t have a neutral density filter to cut down the brightness. (Traditional camcorders have them built in, but for DSLRs you have to physically attach a filter). If you don’t have an ND filter, then ideally you should just stop down and adjust your aperture (i.e. instead of shooting at f5.6, shoot at f8, f10, or even–“gasp”–f16 or higher).

Now, I know precisely why DSLR shooters DON’T want to do this. The smaller your aperture, the deeper the depth of field (DoF), and heaven forbid if you shoot a DSLR with a deep depth of field. Here’s a newsflash people: not every single shot HAS to be a shallow depth of field.

Look at classic, timeless movies like “Citizen Kane” or “It’s A Wonderful Life.” They aren’t filled with a bunch of hyper-shallow DoF shots. In fact, many classic and contemporary films don’t use that hyper-shallow look. I know lots of DSLR filmmakers are just ga-ga over the shallow DoF you get with these cameras, but IMHO it’s way over used. There are other aspects of the visuals that will give it that “film” like look besides DoF (e.g. the color grading, composition, frame rate, etc.)

Here are some tips when I think it makes sense to break the 180 degree shutter angle rule.

- Depth of Field: as I just mentioned, sometimes you’ll want to increase the shutter speed to help you attain a shallow depth of field. If it’s very bright outside, stopping up to f2.8 or f1.4 will totally blow out the visuals. Increasing the shutter speed will reduce the light and compensate for the brightness. Ideally, you should use an ND filter. But on the off-chance you don’t have any, this can work in a pinch. Just don’t go crazy.

- Low Light: sometimes you may be in a setting where the light is pretty low and so using a slower shutter speed will let more light in. Depending on your camera, this will give your image more of a “dreamy” look. When I shot with traditional camcorders, I’d often shoot at 1/15 or slower because I wanted to get those dreamy streaks. I also used to shoot regularly at 1/30 at 30 fps instead of 1/60 because it gives a softer, more film-like look to traditional video. 1/60th has a very “video” look.

- Epic battle scenes: if you’re shooting battle or fight scenes, you may want to use faster shutter speeds to get that staccato look (like the opening of “Saving Private Ryan.”)

If you have other examples of how you break this rule purposefully, and why, hit us up on Twitter.

Shutter speed experiment

Below is an example of where I used a high shutter speed for a very specific purpose. I produced a promo video for an amazing concert pianist in San Francisco, CA. For her promo she played the frenetic piece “Tarantella” by German composer Franz Liszt. The story behind the piece is that if you’re ever bitten by a tarantula, you have to do a crazy and hectic dance to rid yourself of the poison. I used a high shutter speed when recording part of Heidi’s fingers to 1) emphasize the frenetic nature of the piece, and 2) to make her fingers look like crazy tarantulas dancing on the keys.